Here’s another little chunk from the Angertainment draft. Fear and anger have always been an integral part of some forms of entertainment. Here’s a quick summary of how the Greeks and Romans built it into their theatrical traditions.

Part I

Anger and Entertainment: The Classical Era

Quos Deus vult perdere, prius dementat.

“Whom gods would destroy, first they make mad.”

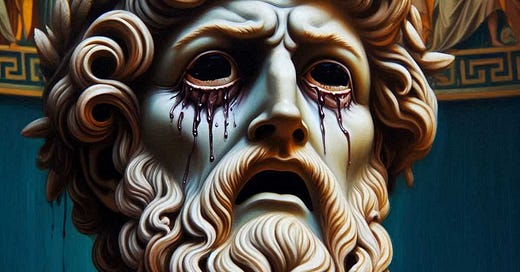

While the Latin text translated above has numerous permutations and possible sources, many scholars trace the sentiment back to Euripides or possibly even Sophocles, and Greek classical theatre. A survey of the leading roles in the Greek dramatic canon reveals a host of characters consumed and ultimately undone by some “tragic flaw.” And most often, the tragic flaw stems from some internal or external conflict that ultimately explodes in anger.

On his return from years of war, King Orestes is slain by his angry, vengeful wife Clytemnestra. A young woman must stand up and speak out against injustice and go to her own death in Antigone. Oedipus, trapped by a curse leveled by the gods must tear his own eyes out.

Even looking back more than two thousand years, the combination of fear and anger provided a critical element in the earliest formal entertainment. Additionally, in considering the evolution of entertainment into angertainment, it’s worth remembering that in Greek theatre (at least in the tragedies), the denouement was understood. The audience was not sitting in suspense waiting to see what was going to happen in these stories. The myths, the characters, their roles and the action that was going to appear on the stage was well known. The dramatic interest flowed from the playwright and the actor’s skill in depicting a familiar story. No surprise endings; the result was known

The Guts of Greek Tragedy

Aristotle, in the Poetics, introduces the idea of “the catharsis of pity and fear.” In his analysis, he saw value in the audience’s experience of these traumatic, mythic events. It was, in a sense, the very first reference to virtual reality.

The audience, living through the actions on stage, experienced the same emotions and absorbed the lessons of the gods. Individuals grew stronger and wiser as they lived through the events that destroyed the tragic hero. Throughout the process, they were able to experience anger, frustration and fear and ultimately, overcome the emotions—the madness—that had inflicted those “whom the gods would destroy.”

The idea of catharsis is useful. For people with pent-up anger, fear or frustration, the idea of letting it go is appealing. The experience of seeing a scene on the stage allows them to live through the experience and feel the emotional release.

Anger is an important component in comedy as well. Classical-era Greeks knew that, too.

Characters are invented and propped up for us to laugh at. Frequently they are dislikable characters. In some cases we are led to despise them. And as a result, when they are thwarted or undone in some way, we are delighted to laugh at their anger. The comic buffoon is often left in a spluttering rage. Audience laugh heartily. And, in a nod to the future of comedy, frequently these comic buffoons had names and character traits gave them more than a passing resemblance to real people. Political satire and political attacks provided content for entertainers two centuries ago.

The Romans Up the Ante: Spectacle and Blood

Our image of Greek theatre is bland. The sun-bleached remains of ancient theatres create a deceptive image. Historians assure us that ancient Greek buildings were splashed with color. The action on the stage was surely cloaked in vibrant costumes. Masks, designed to connect with audience members hundreds of feet from the stage must have added to the spectacle. Yet Greek theatre remained constrained by its own aesthetic limits. Yes, there was violence. But it occurred off stage.

Theatre, as it evolved in the Roman Empire, had no such constraints.

Recognizing the inherent attraction of violent action, Roman playwrights put violent action center stage. Limited only by the stagecraft of the day, Roman theatre audiences were treated to mayhem and murder; scenes drenched in blood and gore.

With the taboo on violent action broken in the theatre; the Romans took dramatic action and spectacle to the next, logical extreme. If theatrical violence was exciting and appealed to audiences—how about the real thing?

Armed men—gladiators—doing battle. Animal combats. What happens when you put a hungry lion in an arena with an angry bull. The famous matchups between lions and Christians.

It is fair to say that the Romans created the first large-scale angertainment industry. Records show that a network of trainers, animal trappers and other suppliers existed to supply Roman “circuses” with their performers. High-ranking, wealthy patrons sponsored the events. Authorities added expendable undesirables to the cast, for use in the shows.

Perhaps these Roman spectacles can be seen as the very beginning of the horror genre of entertainment. Seeing frightened humans confronted by wild animals; is that similar to the cinematic trope that shows an average family threatened by mad killers, possessed being or poltergeists?

The Romans recognized that there is a large appreciative audience for entertainment that featured fear and anger. They were not the first practitioners of this kind of showmanship; just the first to do it on an industrial scale.